Those glory olden days

By Freddy Milton

The other day I accidentally sat talking to a colleague about the past. We came to reflect upon the changes over time and we had just seen the news about the demise of the French comics’ artist Jean Giraud, best known for his western series Blueberry.

We drank the instant coffee and shared our sadness over all the obituaries we were confronted with in the magazines lately, perhaps not so strange since we no longer were yearlings ourselves.

It was extra sad, of course, since the comics’ creators, currently migrating to the eternal drawing boards in the sky, for the most part were the ones we had learned to appreciate during our own youth. Specifically we shared a respect for great storytellers of long epic sagas, such as the Frenchman Jean-Michel Charlier.

My colleague especially appreciated the unpretentious narrative, Charlier represented with his contributions to the Spirou and Pilote weekly comics magazines. During our youth developed a trend in the epic series, where the visual aesthetics often came into focus and overshadowed the narrative, which unfortunately did not always live up to the equilibristic presentation of the visuals. Latin people sometimes overestimate form above content.

A widespread mechanism evolved in albums, that the adventure comics’ audience to a large degree was fascinated by the imagery, whose contribution to the sum total of expression was given too much weight.

I myself suffered from the same flaw of interest, but I excused myself that in the reading process it was important for me to find and develop my own sustainable visual style, if at all possible. So my special preoccupation of the imagery had a professional reason. As for the actual story subject matter that was not crucial to me when I dived into others' production. I was sure to get that matter in place when it came to this for my own part. But in handling the visuals, I needed to learn a lot.

My colleague was confronted with this contemporary reexamination because he was reading through his old comic’ albums in order to revise his collection.

One of the things that did not hold well in the manuscripts, for example, were series from Burgeon and Juillard, which from a good start evolved into boring album stories he didn’t need to keep in his collection today.

For my part I looked with sadness upon the loss of the skilled artists, who each day brought new installments of their infinite continued adventures to the newspapers. What do that kind of talents do today, I wondered? The potential creators would probably still be out there somewhere, if only there was the need for them? The new graphic novels recruit a slightly different kind of comic book artists.

As also shown in my letters from my Sweden years on this site, I was intrigued by experiments with all sorts of genres and styles in those days. I had to try a little bit of everything to find a place where I could create myself a niche that could also preferably develop into a career.

Before it came so far that it landed on the funny animal comics for me, my old colleague and I had exchanged many letters during this experimental phase. At one point he gave me a whole bag of my old letters back, and I have a similar pile of letters from him.

At one time I myself experimented with a western series, and the first episode in the length of an album, The Travers, one can learn about elsewhere on my website. Yes, there were an abundance of try-outs during those years in the 70es, and not only by me but also from a number of other Scandinavian comics artists.

Regarding Charlier, we came during this afternoon conversation on to Blueberry, whose artist, Giraud, had been one of the big trees in the forest of adventure comics’ series creators. My colleague drew attention to the change in style that took place over the fifth album, The Big Showdown, where Giraud really stepped out of Jijé’s shadow and found his own style.

My colleague thought this was related to the fact that Giraud at this time engaged himself more in the storytelling. Thus a prolific person was killed in the course of this album, and my colleague thought this proved his broader involvement. Typical of Charlier, he would probably avoid taking the lives of characters that conveniently could show up at a later date and be used again.

Later, I mentioned this episode to my brother Ingo over the phone and we both reached out and took each of our album number five of the now closed Blueberry saga from the shelf right near our workplace. Ingo leafed through it and agreed that there is actually a smooth transition in pictorial storytelling through this album, where you can see Giraud finds his own style.

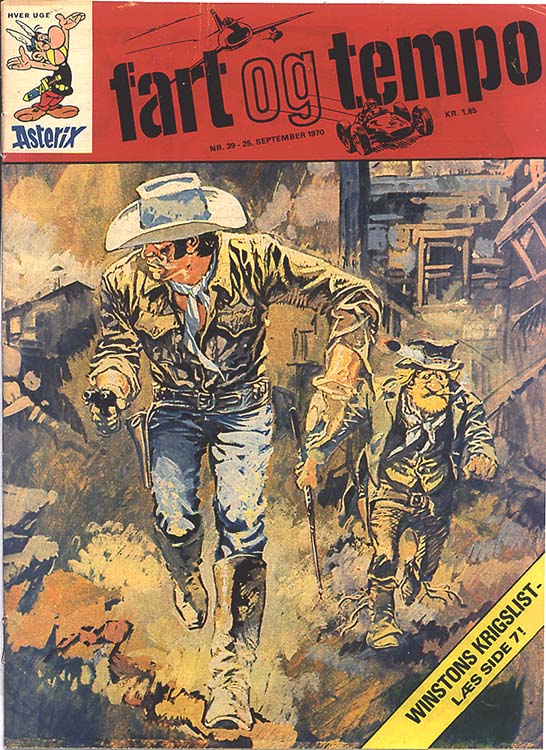

Because of this matter, Ingo and I came to remember a situation where we read the first edition of this and other adventures when they were printed as serialized chapters in the weekly Fart og Tempo comics’ magazine. It meant to us a weekly gathering situation where the two of us actually read the magazine together and commented on what happened in this week’s installments.

For our part it was good quality time in an era before the digital technology changed people's consumption habits forever. Also this fact we could not help but look upon with nostalgic sadness.

Then Ingo urged me to look at page 31 of the album, and we both got to laugh. The past came crashing in over me with the memory of our preoccupation about the creative process we shared at that time in the 70’es.

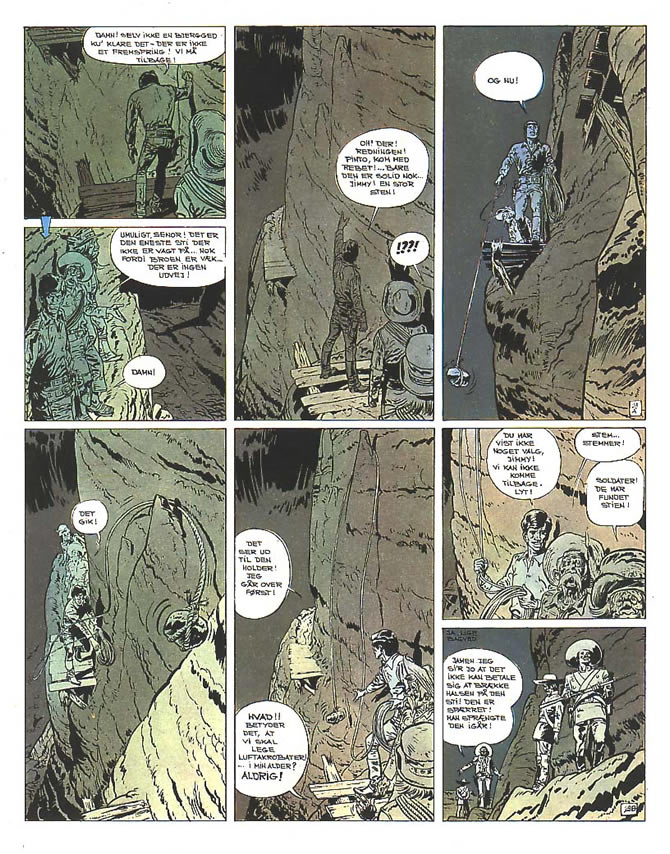

In panel 3 Blueberry throws a rope with a stone over a ledge of rock sticking out. Charlier has very conveniently placed it there, so our heroes can swing over to the other part of a wooden path that someone in a strange way has been able to fix hanging there on the vertical rock surface.

It's just that Giraud then changes his viewing perspective. Looking at picture 4 Blueberry & Co. are suddenly on the other side of the path, because the vertical rock surface is still to the right. It is also there in picture 5, but then Giraud switches back his viewing angle to the starting position, while the rock wall has remained steadfast in its position to the right of the picture.

Ingo and I could instantly recall the discussion we had when we were sitting with Fart og Tempo No. 37 from 11th of September 1970. I had to pay Kr. 1.85 for those 32 pages at the magazine dealer. Even the blurry dark heliographic printing inks had failed to camouflage the view of that infamous rock.

We did not look down upon Giraud because of that, though. After all these things can happen to the best of creators, and when the story was published as an album, they would naturally have discovered the error and mirrored image 3 and 4, so there would be no problems as to the logic within the visuals.

But the album was released, and Lieutenant Winston changed his name to Blueberry, but the rock was still miraculously moved from one side of the ravine to the other, and now over forty years later, I am convinced that it’ll stay there.

This peculiar remembrance I was mostly inspired to tell you because I saw the death notice of Giraud recently. When I saw it many nice memories came to me, and the one with the rock wall was one of those, who had been lingering there in the back of my mind.

As for Fart og Tempo that collection still takes up a whole shelf in my archive room, and it will continue to do so. In that room I also store other matters that has caught my comics fancy so much, that I felt I had to keep them as fond memories. Although the old gems do not all glitter so brilliantly today, it represents, after all, the commitment and research I carried out in my youth in order to find out, how other artists presented their use of the media. I refer particularly to the narrative epic tradition that has always intrigued me the most. And gee, how there were many fanciful contributions in those comics over the years.

Fart og Tempo’was a big hit with Ingo and I, especially because for the first time it showed us comic adventures from Europe where tradition was different than the one we knew from the American comics. European cartoonists were quite different and careful and detailed in their handling of the medium and the coloring was usually varied and harmonious.

Ingo and I was so thrilled by this array of narrative pleasure and ability that we could not help but buy extra copies from the second hand dealers, when they did not cost more than a nickel or a quarter. Since we ended up in a situation where our old rooms had to be vacated a couple of years ago because our childhood home had to be sold, we discovered that we had more nearly complete collections of Fart og Tempo. They took up a lot of space, but the second hand shop Fyns Antikvariat had pity on us and took the many extra copies off our hands so they did not need to be scrapped immediately.

Whether these thin 32-page magazines may interest others today is a tricky question. The most notable series appeared later in album form, where the printing was of better quality. But some stories did not appear as albums in Danish, and there are still sections of the Ringo and Bruno Brazil series by William Vance, which I reread with a nostalgic joy when I plunge into Fart og Tempo.

Another minor error from one of the great masters, I was brash enough to draw attention to, when I sat beside Hermann Huppen during an evening meal for the VIP guests at the first comic strip festival in Horsens, Jutland. I was invited there because I could draw and sit in Donald's car. After receiving the explanation that his not so French-sounding last name was due to the fact that his family came from a German-speaking district, I expressed my condolences with Greg, who had written the script for many of Hermann's previous series. Hermann thanked for the condolences but added that his demise was now mostly his own fault, because Greg had let his body deteriorate. Hermann would probably never be the victim of a similar cardinal sin, so well kept he appeared to be.

Hermann went for stable work routines and had his regular hours of work each day. Ingo added that Mezieres had it the same way and managed to take time off when the workday was over, while others such as Giraud did not feel that way. When Giraud came home in the evening he often continued to draw just for fun, because it was a way of life for him to be drawing all the time.

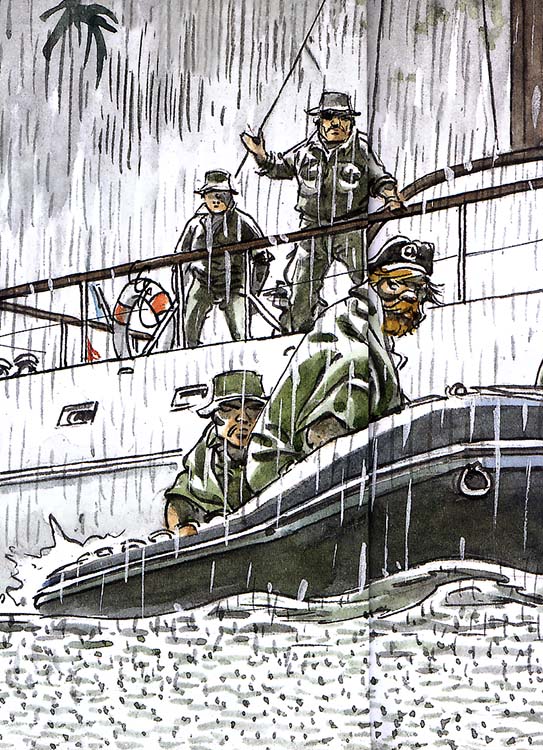

Hermann had after Greg's death taken up the Bernard Prince series again, and as the18th album, The Threat From The River, had just been published in Denmark, I asked Hermann to sign my newly acquired copy. In this context, I could not resist myself but drew his attention to the enlarged panel of ‘Cormoran’, which was on the inside cover and first page before the album's comics pages. It lacked the wire midway under the railing that he usually tended to include there.

Hermann graciously added the missing wire with his felt-tip pen and noticed that I seemed to know the yacht quite well. I had to admit that, and I confessed that it was because I'd allow myself to let the Cormoran have a guest appearance in my forthcoming Gnuff album, The Demon of Dismal Depths, where I needed to draw a yacht from several angles, and my complete collection of Bernard Prince albums provided me with a myriad of angles and perspectives on just that particular vessel. So where did Hermann get his documentation from, concerning that boat?

Hermann answered that the publisher at that time knew someone who had a yacht of this type, so he got half a hundred photos of the yacht seen from all angles, both inside and outside, and that was the basis for Hermann’s many pictures of Cormoran. Whether the original yacht still existed or not, he didn’t know.

I drew Hermann’s attention to the fact that there was some flexibility involved when you draw comics. In the Safari For A Ghost episode the rear deck grows to a substantial size to accommodate the battle scene with the numerous tribe members bordering the vessel.

Hermann looked at me and smiled. An advantage with comics compared to films. You could push the scenery somewhat, so they fit better. The story is more important than props and elements consistency. However people’s priorities differ.

I talked about something similar in my own field where we had a fusspot apprentice of Carl Barks, who wanted every detail to fit with a Master Plan, in contrast to the great master himself, who gladly changed things if it fit better with a good idea he had for a story. Barks was not embarrassed, for example, to give the moneybin the design of a ball, so it could roll along and drop out bank notes, which could subsequently be picked up by a hay combiner, if his funny vision demanded that.

Hermann gave me his standard profile of the Barney character with his soft felt-tip pen and as a trusty old fan boy I felt the day was saved. For a moment we had both been forty years back in time of the golden age of the narrative comics...